This Blog is going to feature reviews mainly and other occasional pieces orientated to the future. Nick Hubble @thehubble101.bsky.social @thehubble101@toot.wales

Prospective Cultures

This is the post excerpt.

This is the post excerpt.

This Blog is going to feature reviews mainly and other occasional pieces orientated to the future. Nick Hubble @thehubble101.bsky.social @thehubble101@toot.wales

Part of my series of posts on Scottish SFF in the run-up to this year’s WorldCon, focusing especially on the work of GOH Ken MacLeod.

(NB. I am discussing the plot and ending of the novel in detail here).

As with its predecessor Learning the World, The Execution Channel was shortlisted for both the BSFA and Clarke Awards. This novel marked a change of direction for MacLeod away from space opera towards near-future thrillers. I recall it was announced at the time that this would be the first of three standalone near-future novels (as turned out to be the case but then he went on to write another two standalones, making five in total). When I first read it, I really liked this novel. It was my preferred candidate for the Clarke that year (although I didn’t feel as upset by its not winning as I did about Intrusion a few years later). While I very much enjoyed rereading it, it now feels slightly different in that we have moved beyond the present depicted in the novel. I’m not saying it’s dated – in fact its vision of international relations especially with respect to Russia and China is as relevant as ever – but it is very much a product of the period in the early twenty-first century when 9/11 appeared to be the defining event. In practice, its significance was superseded not long after the publication of The Execution Channel by the 2007-08 global financial crash. The domestic ‘reality’ of today’s Britain in much more a product of that event and its consequences of austerity, populism and Brexit than of post-9/11 (and post-7/7) tensions. It’s not that the Islamophobia MacLeod touches upon has gone away but rather that, as publicly voiced by the likes of Lee Anderson, it’s become part of a wider culture war being run in the interests of imposing socially conservative authoritarian rule in Britain.

Having said all that, it also needs to be noted that The Execution Channel does directly continue the metaphysical speculations that animate Learning the World albeit within the very different context of the early twenty-first century.

The novel begins with Travis driving north through an England, seemingly under terrorist assault, in a Land Rover, stacked up with jerrycans of fuel, air pistol, bottled water, supplies, camping gear, various currencies and gold coins. He was woken in the middle of the night by a phone call from his daughter Roisin, who is part of a peace camp keeping watch on a US airbase in Scotland, to alert him that the base has been blown up, apparently by a nuclear weapon. From this point we follow not just Travis’s progress (with flashbacks to his backstory) and Roisin’s unsuccessful attempts to avoid being caught by the security services, but also a range of other characters including: Mark Dark an American blogger; Jeff Paulson, some sort of US agent; Maxine Smith, Paulson’s British counterpart; Bob Cartwright, who along with Sarah Henk, Peter Hakal and Anne-Marie Chretien, runs a propaganda and disinformation service; and Alan Gauthier, a colleague of Travis who is both a French and, it transpires, a Russian agent.

Relatively early in the novel, Travis considers both ‘the Matrix theory’ that the universe is a simulacrum and ‘the Planetarium possibility’ that anything beyond the Kuiper Belt is a colossal construction or an illusion. He rejects both but for different reasons: the latter he considers far-fetched and the former disprovable. What troubles him about both is their popularity: ‘It was as if people wanted to doubt the reality of their lives, and the solidity of things’.

The action plot of the novel is an entertaining linked sequence of events and chases which work to bring Travis, Roisin, Smith, Paulson and Gauthier all together for a climactic encounter in Norway. But there is also a related trail of information in which Cartwright and his team try to plant false information via Dark’s blog, while Dark processes this disinformation to reverse-engineer his way to what has actually happened. For example, when Dark is ‘leaked’ highly classified military documents, he concludes they are too good to be true and therefore part of an attempt to discredit him, which in turn means that some of his speculations about what happened at the Scottish airbase must be correct. Later, when Cartwright checks Dark’s blog to see if he had anything to say about the forged documents, he finds that Dark has written a long post, which begins:

We’re living through an odd moment, folks. Until we know who or what was behind the Leuchars explosion, we don’t know what world we’re in. Somebody knows. It could be a handful of people or just one. They’ve already opened the box and seen if the cat’s alive or dead. The rest of us don’t know, and until we do the wave-function hasn’t collapsed. Whoever knows the truth and exposes it – and it could be just one person – will change the world and the future for us all.

The post, which is provided in full as a text within the main text, goes on to illustrate its points by reference to the 2000 US election, which was decided by a relative handful of votes in Florida, and 9/11. The plot twist in this is that The Execution Channel is revealed to be an alternate history in which the Democrat Al Gore won in 2000 and 9/11 manifested differently to our timeline, as a consequence of Gore’s cruise missile strike killing Bin Laden. The irony is, of course, that this different 9/11 still leads to the invasion of Afghanistan and then Iraq, although also further, more divergent consequences. There’s more than one thing going on here: a nice take on conspiracy theories, a criticism of US foreign policy (which carries on much the same regardless of which party holds power), and a reflection on the interaction between historical contingency and deeper underlying trends. However, there is also a more radical argument that ‘reality’ is not simply a product of linear causality but an oscillating range of possibilities that can only cohere into ‘stable’ being through human observation that collapses the waveform (as in the ‘Shrödinger’s cat’ thought experiment; a recurrent theme in SF – see the post I linked in the quote above, in a place where Dark’s fictional blogpost would have had a link). This type of reality corresponds with the idea expressed by Atomic Discourse Gale in Learning the World that if you do find fairies in the back garden then actually the world you are living in is different to the one you thought and you need to begin learning it afresh (and learning in this context is not value neutral; MacLeod also sees it as a moral response). In the context of The Execution Channel, the point being made by Dark – and I think by MacLeod – is that until it is known exactly what happened in the explosion at the beginning of the novel, reality is mutable because if it is something hitherto unknown – and it becomes clear very quickly that it wasn’t a conventional nuclear weapon – then we know that we are going to discover something that means the world is not the way we thought it was, and we’re going to have to relearn it.

There’s nothing unusual about this way of thinking. It is central to science, in which new discoveries continually force scientists to relearn the world. It is however more alien to ‘commonsense’, tradition and other ingrained cultural ways of viewing the world (although even religions adapt to changed circumstances). Furthermore, this kind of worldview is not entirely consistent with how we approach literature, even SF which is supposedly rooted in cognitive estrangement, or certain forms of Fantastika which are open to weirdness. However, MacLeod doesn’t foreground estrangement or weirdness in the same way that writers such as, for example, (in their different ways) Christopher Priest or China Miéville were doing across the same period. His novels – especially the five near-future standalones – are superficially fairly straightforward combinations of plot- and character-driven near-future thriller. Therefore, their general metaphysicality and context of unstable, changing ‘reality’ that has to be continually adapted to, can have the effect of making it look like he is regularly resorting to the use of an ‘unearned’ deus ex machina. This holds, to one extent or another, for all five of these standalones. The key moment in The Execution Channel is at the climax when, seemingly out of nowhere, as everyone waits for nuclear Armageddon, it transpires that, rather than a number of Russian, Chinese and North Korean cities having been obliterated by a pre-emptive US first strike, they have in fact simultaneously launched into space using a revolutionary new plasma focus-fusion technology (as recorded in a series of lovingly pastiched press releases from the three regimes that MacLeod devotes several pages to).

However, while this development does catch the characters we’re rooting for – Travis and Roisin – by surprise, it’s not untrailed and, as acknowledged by the final chapter, is actually central to the novel’s overall logic that ‘life is elsewhere’. Not necessarily because, as is teased, we might be living in a simulation but because there is no central narrative to follow. Some of the protagonists – Travis, Roisin, Mark, Anne-Marie – learn this new world and some of them don’t. In this respect, the novel, despite being a thriller, also manages to be (as most of Macleod’s work) a comedy of manners.

As a final note, the spy element of the novel, which seems to turn on the Russians having manipulated the French into taking over the CIA’s terrorist network in the UK in order to trigger havoc across motorway junctions and oil refineries, dovetails with the idea of the mutability of the world to show how such operations take on a life of their own (in the same way that historic CIA operations in Afghanistan have profoundly changed the world). In this respect, MacLeod provides a useful antidote to the stories in the media that there was Russian interference in Brexit and Trump’s election or, more recently, that the Chinese are behind the hacking of the British Army pay system. The problem with these stories is not that there might be no truth in them but rather that they simplify our conception of the world into a straightforward choice which is not even between right and wrong but between ‘our’ country and a supposedly ‘enemy’ one. At one point in the novel, Travis rationalises the fact that he is an Englishman working as a French agent by thinking: ‘The thing he liked about France was that it was French. The thing he hated about England was that it wasn’t English … At some point England had simply failed itself.’ He realises that the difference between him and Roisin is that while she was prepared to work against the government and the state (i.e. because they are right-wing and imperialist), ‘she would never have thought her enemy was England, or even Britain … She had believed that people could be persuaded to oppose the war’. He doesn’t believe that. The point being that the world changes once you no longer believe in your country. The Execution Channel shows believing in your own country to be a category mistake. I will come back to the matter of England/Britain when discussing MacLeod’s subsequent novel, the Scottish-set The Night Sessions. However, before I get to that, I’m going to be posting on The Corporation Wars trilogy at some point over the next few weeks.

Part of my series of posts on Scottish SFF in the run-up to this year’s WorldCon, focusing especially on GOH Ken MacLeod.

Moving on from my post on MacLeod’s Newton’s Wake, here are my thoughts (including discussion of the ending and other major plot points) on its immediate successor, Learning the World: A Novel of First Contact, which was shortlisted for both the Clarke Award and the BSFA Best Novel and won the Prometheus Award (the third of MacLeod’s three victories in that award). As with Newton’s Wake, I think I enjoyed re-reading Learning the World even more than I did when it came out. I should note at the outset that it is tremendous fun: full of wit, joy and lively exchanges between a range of great characters. It is also a novel of ideas.

The novel opens with a blogpost dated 14 364:05:12 written by 14-year-old, Atomic Discourse Gale, who is one of the younger ‘ship generation’ born on the generation starship But the Sky, My Lady! The Sky!. The dating is that of the human space age, so presumably starts from 1961 or thereabouts, meaning that the novel is set in the one-hundred-and-sixty-fourth century, which I think makes it the most future-set of all MacLeod’s fiction by some distance.

Chapters set on the ship, featuring Gale, her care-mother Synchronic Narrative Storm, the crew member Horrocks Mathematical and the enjoyably-annoyingly-Heinleinian ‘Constantine the Oldest Man’, are interspersed with chapters set on a planet, ‘Ground’, in which Darvin and Orro, who have wings and can fly, are engaged in research to develop heavier than air flight. Darvin’s main area of research is astronomy and, in his attempts to discover a new planet within his solar system, he comes across an approaching object, which first he takes for a comet, but then (with Orro’s mathematical help) realises must be a spaceship. It is of course the But the Sky, My Lady! The Sky! and so the scene is set for the eventual ‘first contact’ between the humans on the generation ship and the ‘alien space bats’.

Thematically, the novel works by comparing the two societies and slowly subverting our preconceptions so that we come to realise that the people of Ground, although only at the point of inventing aeroplanes (which we realise they have achieved when they fly over Darvin’s head later in the novel), are in many ways more emotionally mature (‘more rational and kinder’) than the humans and, by implication, better scientists. As the moment of first contact gets nearer, it is the people of Ground who come together in a unified approach and the humans who split into factions. At one point, Darvin (who along with Atomic Discourse Gale is the main viewpoint protagonist) speculates on how his society might have been very different ‘if there had been no trudges’ – trudges are tractable beasts of burden that people of ground use as labour. He remembers how some ‘engineering tales’ (i.e. the space-bat equivalent of SF) posit that there would have been slavery, which would probably be superseded by some sort of payment system that enforced labour through debt (in other words, the western capitalist system on Earth).

In contrast, the humans on the generation ship, although descendants of such as Earth, seem to the products of a slightly different economic system. As Gale outlines at one point: ‘Law of association. Extended markets. Division of labour. Mutual benefit’. Indeed, a complex economic system of markets and futures not only flourishes but actually enables the operation of the ship. However, this system is not capitalist, but in some way postcapitalist. It reminds me of some of the ideas in Cory Doctorow’s Down and Out in the Magic Kingdom, but also the attempt to use algorithms and market-style operations to create a post-scarcity society in the USSR as outlined in Francis Spufford’s Red Plenty. I’d have to do some more research on economics (which I should) to write more but I think some of ideas also come out of the Scottish enlightenment – Adam Smith and David Hume et al. In this respect, Learning the World is yet another of MacLeod’s Scots-in-Space Operas. On this point, it should be noted that there is a (female) character called Amend Locke, which is MacLeod’s twitter handle, on the ship and I read this as an acknowledgment of this economic/philosophical/political which amends the arguments of Locke to set out its positions. When I originally read the novel, I found the markets aspect a bit alienating but my interests have shifted over the years. Intervening events make me more receptive to the arguments today than at the time.

So, on the one hand, the ‘space bats’ are both more rational and kinder because they have no history of slavery and there is a lightly traced-out political-economic framework that underpins why that is the case. However, there is also a metaphysical argument, which recurs throughout MacLeod’s body of work but is probably most clearly explained in this novel. It is quite often this feature of his work that sometimes cause critics to struggle with aspects of it, as has been the case with several subsequent novels, notably The Execution Channel (2007) and Intrusion (2012). The key exchange here is one that takes place between Gale and Horrocks about a third of the way through the novel:

‘You remember when the transmissions were detected, you made a joke that they might be from aliens?’

‘I did? I must have better foresight than I thought.’

She looked impatient. ‘The whole point of your joke was that there are no aliens. It wouldn’t have been funny otherwise. Just like if my care-mother had said that something I’d lost in the garden had been taken by the fairies, or the hideaways. If we found fairies in the garden, or hideaways, it would tell us that the world was quite different from what we had imagined. It wouldn’t just be a world that had fairies in it, like a different kind of bird or something. It’d be a different kind of world, a world in which fairies could exist.’

(This same example is an actual plot point in Intrusion, where it forms part of an argument about the kind of world we live in and the pointlessness of micromanaged politics – à la New Labour – which fundamentally mistake the kind of world we live in). The point of Learning the World – which is not just the title of the novel but also of Gale’s blog – is that is a scientific progress, which means that if aliens suddenly turn up, it’s not just a question of treating them like another species or comet hitherto undescribed. Rather, the appearance of aliens would mean that the world does not work in the way that we thought it did and therefore we have to learn it anew. While Gale understands this, many of her fellow humans don’t get it. On the contrary, it’s almost second nature to the ‘space bats’. The second the trudges become intelligent and rational – due to Constantine and his faction ‘reverse engineering from the language module’ – Darvin and his people very quickly come to the rational acceptance of the fact that the world has changed and they let the trudges free and start treating them as fellow conscious beings. The equivalent in human society, would be realising that the existence of rapid climate change, or of nonbinary and multiple genders, indicates that we don’t live in the same world that we thought we did and setting out to relearn the world and make radical adaptions to it (and not reacting by trying to force things back to ‘normal’, which in effect entails closing one’s eyes and wishing very hard that the world hasn’t changed).

When I first read it, I was dissatisfied with the ending in which Gale finishes her blog with a final post before leaving with the ship for the next system rather than staying in the solar system of Ground as we have been expecting throughout the novel (I should note that others read the end differently to me). Now, I think this is actually a brilliant ending in what is a superbly structured and realised novel. Gale leaves us with two theories to explain what has happened and why the ‘space bats’ are ‘more rational and kinder’. The first, specific, theory is, as Darvin had speculated, that they bore the yoke and therefore had an easier ‘ascent’. The second is a metaphysical theory:

Just as the birth of universes from black holes selects over cosmic time for universes with laws of physics such that black holes can be formed, hence universes with stars and galaxies, so the birth of universes from starship engines selects for more universes in which starships can exist. And what more likely universes to have many starships in than ones in which intelligence emerges all over the place at almost the same time?

This hypothesis comes from another of the twists at the end of the novel that the space bats identify other galactic intelligences even before the climactic moment of first contact. Once you live in a world with other alien intelligences, you live in a world with lots of alien intelligences. Gale’s ponders that ‘perhaps those like us who come first are changed the least’ and perhaps doomed to always encounter wiser and kinder species. This would represent a radical decentring of the human subject but at the same time a massive expansion of our horizons. That’s why I think it makes sense that she chooses to travel on beyond the limits of the ‘world’ that she grew up in.

Now that EasterCon is over (report to follow) and we’re in the run-up to this year’s WorldCon in Glasgow, I’m planning a number of posts on Scottish SFF, including some of my favourite writers such as Naomi Mitchison, Iain Banks, James Leslie Mitchell (AKA Lewis Grassic Gibbon) and, of course, Guest of Honour Ken MacLeod. (I’m aiming for 1000-1500 words to keep them relatively on point. These posts are going to include some spoilers, so, if you’re adverse to that, be warned).

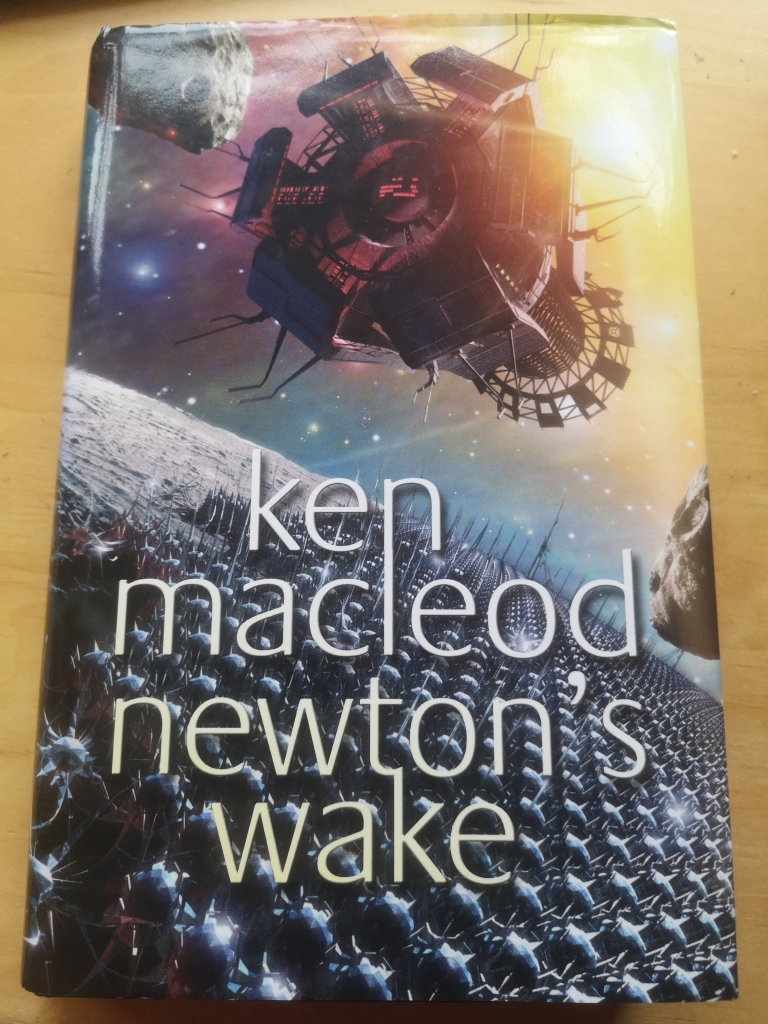

To get this series underway I’m beginning with a post on MacLeod’s Newton’s Wake, which was first published 20 years ago. I’ve picked this because Ken was talking about it a bit at EasterCon in the session on the opera, Morrow’s Isle, for which he has written the libretto (music and choreography by Gary Lloyd and Bettina Carpi of Company Carpi) and which will be performed in Glasgow on the Thursday of the WorldCon. Newton’s Wake is, of course, subtitled A Space Opera and contains an opera within it, as well as the wonderful Shakespearean pastiche, The Tragedy of Leonid Brezhnev, Prince of Muscovy. In retrospect, it is also perhaps the novel that most clearly links some of the themes of The Fall Revolution quartet (1995-9) and the Engines of Light trilogy (2000-2) with his current Lightspeed trilogy (2021-4).

It’s 2367. There’s a whole galaxy, a whole new world out there. Wormholes and starships and endless youth and resurrection…

Re-reading Newton’s Wake over the last few days has been a complete joy. I think I enjoyed it more than when it came out; partly because it serendipitously ties in with themes I’ve been thinking about recently. It’s barely a week ago on the Friday of EasterCon that I was talking about Hao Jingfang’s Jumpnauts (first published in English in March 2024) and saying that it was a novel that could only be written in a country that still believed in the future because of experiencing unprecedented social, economic and technical progress over the last half century. Reading Jumpnauts – with its vision of humanity (potentially at least) ascending to the next level of civilisation by learning to share information telepathically as a means of interacting with the intelligent substrate of the universe – was, I said, the nearest we could come today to the experience of reading Wells in the early twentieth century. Then, I read Newton’s Wake in which we are told towards the end that:

There are good and bad things, but no good or evil will. There’s only intelligence, and stupidity. Stupidity is what we had as humans, and intelligence is what we and everyone else now has, however they began.

In other words, the dream of the (transhuman) future is still alive in twenty-first century Scotland. Admittedly, the twenty-first century in the novel doesn’t go that smoothly with total nuclear war breaking out after an American military AI becomes self-aware triggering a pre-emptive first strike on the USA by the combined forces of Russia, France and Britain, and then the subsequent retaliatory strike (which is replayed in virtual reality about three paragraphs after the passage I have just quoted). However, various human factions survive off planet and it is these who animate the novel’s twenty-fourth-century present. These factions include America Offline, the (mainly Japanese) Knights of Enlightenment, the communist DK (‘we think it stands for Demokratische Kommunistbund or maybe Democratic Korea or Kampuchea for all I know’) and, of course, a Scottish ‘family business’, the Carlyles, who control a skein of wormholes and their gates. The novel begins with the main protagonist (of an ensemble cast), Lucinda Carlyle, running into trouble on a new planet, Eurydice, when she discovers a lost human colony, who in the intervening years have developed a technologically advanced (although unlike the other factions, they don’t have FTL spaceships) post-scarcity society.

In case it isn’t clear, I should point out that the novel is a social satire which plays out at some speed, pausing only for the dramatic and musical interludes as mentioned above. In this respect, the reading experience is not so much akin to early Wells as to the somewhat more worldly-wise social comedies of later years, such as The Autocracy of Mr Parham (1930). Certainly, the ageing author of genius would enjoy the party scenes MacLeod wittily stages in the delightfully hedonistic capital of Eurydice, New Start. A wide variety of issues – such as whether New Start’s cornucopian capitalism and reputational economy is a utopia – are covered with a sure light touch. Eurydice is a colony of ‘runners’ in that is founded by those who chose to run away from the solar system rather than fight back against the accelerating AI and posthuman intelligences that are undergoing the ‘Hard Rapture’, but it has its own ‘returner’ minority, who are inclined to cut deals with the Carlyle’s in pursuance of their aim of ‘getting them all back’ – that it is recovering all the human lives digitally uploaded by the AIs on Earth shortly before everyone was incinerated.

The playwright and impresario, Benjamin Ben-Ami, resurrects the returner singing act of Winter and Calder (they were ‘big in the Asteroid Belt’) for a new opera designed to cash in (reputationally) on the tensions created by the arrival of the Carlyles (shortly followed by the Knights, the DK and AO) on Eurydice. We learn that that Winter and Calder were not downloaded from a direct upload but resurrected (by the ‘Black Sickle girls’) with a neural parser which matches neural structures with known inputs. In other words, their synthetic memories were reverse engineered from their songs, videos, sleeve notes and press releases, much to Lucinda’s disgust: ‘They had prosthetic personalities. They had false memories. Without reliable memory there could be no identity, no continuity, no humanity.’ It’s an interesting concept which made me think about the origin of the companion app, Replika, in founder Eugenia Kuyda’s creation of an AI chatbot from the texts of a dead friend in order to talk to him again. Maybe one day we will get them all back, at least those with a sufficient textual record. Anyway, Lucinda gets over her prejudices, in part due to undergoing her own death during a closed-room heist and having to be resurrected. Cyrus Lamont’s predilection for sex with his own ship avatar is also endorsed by the text in the happy ending he finds with the transhuman, and entirely metal, Morag Higgins. There’s a nod to Blade Runner, in Higgin’s desire ‘to feel solar wind in my hair. See the stars with my own naked eyes, in vacuum. See what an FTL jump really looks like. I’d hold my mouth open and catch quantum angels like midges.’ In short, Newton’s Wake is a triumphant distillation of Macleod’s body of work, encompassing, what the New Scientist described as, his wit, intelligence and political challenge.

Indeed, rereading the novel reminds me of what an interesting choice he is as a WorldCon GOH in 2024. For anyone sitting in the UK or the US looking at the world around us, we see the prospect of a dystopian future fought over by tech billionaires and out-of-control populism, while around us the Pax Americana goes horribly, horribly wrong. MacLeod’s whole body of work, in which the political arguments of the 1970s (including those of Marxism and revolutionary socialism) still continue to play out across the universe, offers us a completely alternative (Scottish) paradigm in which everything from AI to transhuman sexuality is still available to further the cause of social needs. If we can only find our way to the post-scarcity future, there won’t ever be any need to look back again.

Some items appear under more than one heading. This list will be updated (periodically) as new posts appear.

Road to Glasgow 2024 (Scottish SFF)

MacLeod, Ken. The Execution Channel (2007)

MacLeod, Ken. Learning the World (2005)

MacLeod, Ken. Newton’s Wake (2004)

Mitchison, Naomi. The Corn King and the Spring Queen (1931)

Interwar Novels as SF/F

Gibbons, Stella. Cold Comfort Farm (1932) as SF Text

Jameson, Storm. In the Second Year (1936) as SF Text

Macaulay, Rose. What Not (1918/2019)

Mitchison, Naomi. The Corn King and the Spring Queen (1931) as SFF Text

Woolf, Virginia. A Room of One’s Own (1929) as SF Text

‘1970s Feminist & Utopian SF’

Le Guin, Ursula K. The Left Hand of Darkness (1969/2017)

Le Guin, Ursula K. The Dispossessed (1974)

McIntyre, Vonda N. The Exile Waiting (1975/2019)

McIntyre, Vonda N. Dreamsnake (1978/2016)

Russ, Joanna. ‘When it Changed’ (1972) – discussion and reflection on teaching it

Fiction Reviews

Albinia, Alice. Cwen (2021)

Allan, Nina. Ruby (2020)

Atwood, Margaret. MaddAddam (2013)

Byrne, Monica. The Girl in the Road (2014)

Charnock, Anne. Bridge 108 (2020)

Dick, Philip K. Electric Dreams (2017)

Doctorow, Cory. Down & Out in the Magic Kingdom (2003)

Faber, Michael. The Book of Strange New Things (2014)

Hall, Sarah. The Carhullan Army (2007)

Hurley, Kameron. The Stars are Legion (2016)

Hutchinson, Dave. Europe in Winter (2016)

Ings, Simon. The Smoke (2018)

Jones, Gwyneth. Kairos (1988/1995/2021)

Jones, Gwyneth. The Grasshopper’s Child (2014)

Lovegrove, James. Sherlock Holmes and the Sussex Sea Devils (2018)

Macaulay, Rose. What Not (1918/2019)

McAuley, Paul. Beyond the Burn Line (2022)

MacLeod, Ken. Newton’s Wake (2004)

Muir, Tamsyn. Gideon the Ninth (2019)

Penny, Laurie. Everything Belongs to the Future (2016)

Priest, Christopher. The Adjacent (2013)

Priest, Christopher. Airside (2023)

Priest, Christopher. Expect Me Tomorrow (2022)

Priest, Christopher. The Gradual (2016)

Pulley, Natasha. The Watchmaker of Filigree Street (2015)

Roberts, Adam. Bête (2014)

Roberts, Adam. By the Pricking of Her Thumb (2018)

Roberts, Adam. Haven (2018)

Saulter, Stephanie. Regeneration (2015)

Sullivan, Tricia. Occupy Me (2016)

Sullivan, Tricia. Sweet Dreams (2017)

Suzuki, Izumi. Terminal Boredom (2021)

Swainston, Steph. Fair Rebel (2016)

Tuttle, Lisa. The Curious Affair of the Somnambulist and the Psychic Thief (2016)

Warner, Sylvia Townsend. Kingdoms of Elfin (1977/2018)

Whiteley, Aliya. Skein Island (2015/2019)

Reviews of Short Story Collections

Mayer, So & Adam Zmith (eds). Unreal Sex: An Anthology of Queer Erotic Sci-Fi, Fantasy, and Horror (2021)

Penner, Robert G. Big Echo Anthology (2021)

Poetry Reviews

Banks, Iain and Ken Macleod. Poems (2015)

Non-fiction Reviews

Bould, Mark, Andrew M. Butler, Adam Roberts and Sherryl Vint (eds). The Routledge Companion to Science Fiction (2009)

Gifford, James. A Modernist Fantasy: Modernism, Anarchism, & the Radical Fantastic (2018)

Jones, Gwyneth. Joanna Russ (2019)

Kincaid, Paul. Iain M. Banks (2017)

Lovegrove, James. Lifelines and Deadlines: Selected Non Fiction (2015)

Morgan, Glyn (ed). Science Fiction: Voyage to the Edge of the Imagination (2022)

Morgan, Glyn & C Palmer-Patel (eds). Sideways in Time: Critical Essays on Alternate History Fiction (2019)

Roberts, Adam. Rave and Let Die: The SF & Fantasy of 2014 (2015)

Roberts, Jude and Esther MacCallum-Stewart (eds). Gender and Sexuality in Contemporary Popular Fantasy (2016)

Samer, Rox. Lesbian Potentiality & Feminist Media in the 1970s (2022)

Wolfe, Gary K. Bearings (2010)

Exhibition Reviews

A Tale of Two Fantasy Exhibitions: Rome and London (2023)

GENDERS: SHAPING AND BREAKING THE BINARY (2020)

Awards & Shortlist Reviews

BSFA Awards Best Novel Shortlist (2024)

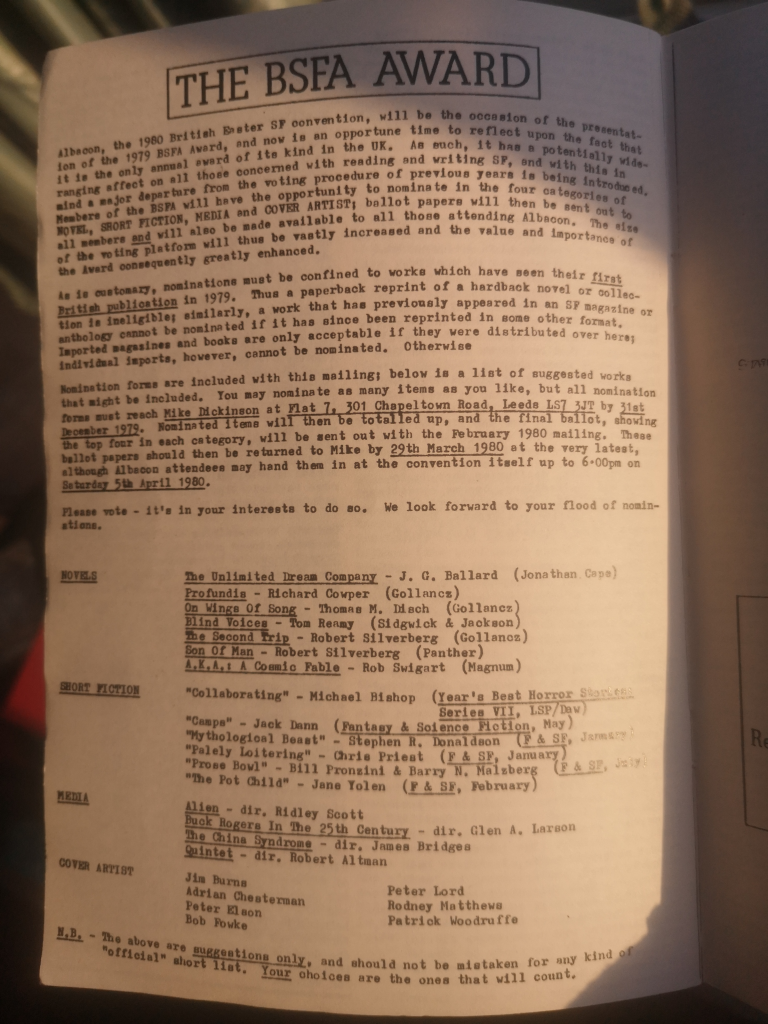

BSFA Awards: History and New Categories (2023)

Politics and Literature: Reviewing, Criticism and Awards (2023)

Talk on the Clarke Award, 8 September 2023. (2023)

‘The Clarke Award and I: A brief excursion into autobiography, motivations and plans’ (2023)

Hugo Award Best Novel Shortlist (2023)

Clarke Award Shortlist Part One (2023)

Clarke Award Shortlist Part Two (2023)

Brief Thoughts on the Clarke Award Submission List (2023)

Locus and Nebula Shortlists (2023)

BSFA Awards Best Novel of 2022 Shortlist Part One (2023)

BSFA Awards Best Novel of 2022 Shortlist Part Two (2023)

BSFA Awards Best Novel Shortlist Reviews Postscript (2023)

Some Thoughts on the Longlist for BSFA Best Novel Award (2023)

New Publication: ‘Thirty Years is Ample Time: The Clarke Award and Literary Science Fiction’ in Andrew M. Butler and Paul March-Russell, eds, Rendezvous with Arthur C. Clarke: Centenary Essays (2022) (posted 2023)

Looking Back on the 2022 Clarke Award (2022)

BSFA Awards Best Non-Fiction of 2021 Shortlist (2022)

BSFA Awards Best Non-Fiction of 2020 Shortlist (2021)

Hugo & Clarke Awards 2020 Best Novel Shortlists Part One (2020) – i.e. a review of the three novels on both shortlists.

Hugo Award 2020 Best Novel Shortlist Part Two (2020)

Clarke Award Shortlist 2020 Part Two (2020)

BSFA Awards Best Novel of 2019 Shortlist Part One (2020)

BSFA Awards Best Novel of 2019 Shortlist Part Two (2020)

BSFA Awards Best Shorter Fiction of 2019 Shortlist (2020)

BSFA Awards Best Non-Fiction of 2019 Shortlists (2020)

Gender Diversity and ‘Literary SF’ in the run-up to the 30th Anniversary of the Clarke Award (2016). (updated 2020)

Essays and Conference Papers

Christopher Priest: A Remembrance (and a review of Airside) (2024)

BSFA Awards: History and New Categories (2023)

Politics and Literature: Reviewing, Criticism and Awards (2023)

The Generic (SFF) Formula of the Fool’s Errand (posted in 2023)

Some Thoughts on SF Handbooks (2023)

Christopher Priest, ‘Expect Me Tomorrow (2022) and Some Thoughts on Temporal Structure and Whether It is an ‘Overshoot Novel’ (2023)

Christopher Priest and (the Persistence of) the New Wave (2022; updated version of 2016 article in Foundation)

Brief Notes on Cory Doctorow’s Down & Out in the Magic Kingdom (2003): Meritocracy and Reputational Economy (2022)

‘The Woolfian Century: Modernism as Science Fiction, 1929–2029’ (2022) – online article

There is no such thing as Science Fiction/ Modernism/ English Literature (*delete as appropriate) (2022)

The Break-Up of the English Class System as a Comfort Read (2021) – conference paper

‘“Where will it all lead?”: Gwyneth Jones’s Life’ (2021) – conference paper, academic track, DisCon III

Expanded version of my paper on Generation X for ‘Douglas Coupland and the Art of the “Extreme Present”’ (2021) – conference paper

‘The Radical Utopias of Ursula K. Le Guin’ (2021) – Tribune

‘How Sci-Fi Shaped Socialism’ (2020) – Tribune

‘Switching Between the Binaries’ (2020) – conference paper (including Mitchison, Banks, Justina Robson’s The Switch)

Gender Diversity and ‘Literary SF’ in the run-up to the 30th Anniversary of the Clarke Award (2016). – updated (2020) version of Foundation article from 2016

The Gradual (2016) by Christopher Priest: Thoughts on the Dream Archipelago Fictions (2020)

The Legacy of 2000AD: Review-Essay (Part One) (posted 2020; originally 2014)

The Legacy of 2000AD: Review-Essay (Part Two) (posted 2020; originally 2014)

‘Our unique isolationist Brexit cultural identity’: Thoughts about 2000AD (aka Part Three) (2020)

Proletarian Modernism (Edinburgh University Press Blog, 2017)

“The Kind of Woman Who Talked to Basilisks”: Travelling Light Through Naomi Mitchison’s Landscape of the Imaginary (The Luminary 7, 2016)

The Flowers of War (essay about Sarah Hall’s The Carhullan Army – originally published in Vector 258)

Five English Disaster Novels, 1951-1972 (originally 2005 in Foundation)

Con Reports, Annual Reflections Etc.

Looking Forward at 2024, Or, Should Galadriel Take the Ring? (2024)

Eastercon 2023: ‘And now the conversation has ended …’ (er, not quite just yet) (2024)

2022 Round-Up (2022)

Notes from Chicon8 (2022)

‘Where are the Workers: Class and Caste in SFF’ (2022; this was a panel I was on at Eastercon)

My 2021 in Review (2021)

‘“Where will it all lead?”: Gwyneth Jones’s Life’ (2021; conference paper, academic track, DisCon III)

ConFusion Eastercon 2021 Report (2021)

What I Did in 2020: A Brief Cultural Review (2020)

A Partial Report on Sci-Fi London and the Orcs and Replicants (2020)

Podcasts

Talking about the intertwined history of speculative fiction and socialism (especially William Morris’s News from Nowhere) on The Last Refuge of the Incompetent (2021)

Talking about my book The Proletarian Answer to the Modernist Question on Suite 212 (2019)

Here is my review of the shortlist for the BSFA Award for Best Novel published in 2023 to be awarded at Eastercon 2024. My review from last year, when I was going for complete scientific analysis, was spread over three posts: Part One, Part Two, Postscript. This year I’m keeping it simple with just the one post consisting of 3-400 word reviews of each novel and a short discussion at the end

Geoff Ryman, Him (Angry Robot, 366pp.)

I’m here drawing on a review yet to appear in the BSFA Review: What I particularly love about Angry Robot is that every novel has a backcover blurb feature (‘File Under: …) listing topics under which it can be filed. In the case of Him these are ‘The Greatest Story Never Told / Child of the Faith / Apocrypha / Herstory’. This is funny as Him is a novelisation of the life of Jesus but with the twist that Jesus, or Yeshu, is a trans man. ‘Herstory’ is still appropriate as a description because the novel is narrated from the perspective of Yeshu’s mother, Maryam. Indeed, one of the key points of the novel is that it is Maryam who records what will become the message of the Gospels by writing down what Yeshu says.

I went to Sunday School as a child and my mum was a Sunday School teacher, so I know these stories fairly well even though I’ve spent forty years outside the church. Over the years, however, the stories have become mixed in with popular-culture retellings from Jesus Christ Superstar to The Life of Brian. I suspect I’m not the only one for whom the sermon on the mount immediately conjures thoughts of blessed cheesemakers. Likewise, I’m pretty sure that henceforth I’ll forever imagine the Virgin Mary stuttering while explaining to her uncle, the Kohen Gadol, how ‘the … the pregnancy came about in an unusual way’. Discussing it with his wife afterwards, he says, ‘She’s mad. I don’t suppose you know of any man mad enough to marry her?’. ‘There’s Yosef,’ his wife replies. This is Yosef the Levite, who goes around claiming that Adam and Hawa were not a man and a woman but ‘neither or both’. Subsequently, Maryam’s parthenogenetically born (and therefore identical to her) daughter, Avigayil, grows up only to declare that she is a boy. When, following a ten-page gap, the text shifts to using male pronouns, it feels like a significant realignment of reality, as though the relationship between God and the world has changed.

This change is further demonstrated when Elazar (Lazarus) is brought back from the dead. Like Buffy, he comes out of the tomb complaining that he has been dragged against his will from heaven. The point of this demonstration, as ‘the Son’ explains, is that God has indeed changed and ‘now allows your spirit to live after death as you yourself’. By treating this old and, by now, well-worn story as genre, Ryman gives it renewed meaning as twenty-first century SFF. Only science fiction can save us now.

Gareth Powell, Descendant Machine (Titan Books, Kindle ebook edition, pp.)

This is another instalment in the Continuance series that began with Stars and Bones, which was of course on last year’s shortlist. The novels in this series can be read in any order so it is fine to start with Descendant Machine, which is a fast-paced space opera. A brief introduction frames the novel as being narrated by the V[anguard] S[cout] S[hip] Frontier Chic. The main protagonists are Nicola Mafalda, the navigator of the Chic, and Orlando Walden, a young physicist being taken by Mafalda and the Chic from the Thousand Arks of the Continuance (on which the homeless remnants of humanity are slowly traversing the universe) to Jzat in order to study the Grand Mechanism. Things start to go wrong once Mafalda begins the return journey after dropping off Walden. The Frontier Chic is attacked by a Jzatian gunboat and is only able to keep Mafalda alive and escape by taking very drastic action indeed.

Although Mafalda survives and lives to ultimately sort out, after many adventures, the resultant rapidly escalating situation, her relationship with the ship, as indeed with just about everyone else, does become a bit prickly. She’s an engaging character, whom I had no hesitation in making the object of my readerly identification, but I did wonder if more mileage could have been gained by keeping her gender ambiguous for most or all of the novel (Nicola, of course, being a masculine name in Italy). Aside from the introduction which refers to her as Ms Mafalda (although I only noticed this when I went back to look at it again), there are a good 50 pages at least before a pronoun is used at all and I was enjoying the uncertainty until the feminine pronouns started appearing. Having said that, she’s still a pretty cool, gender-nonconforming character, as one might expect in the SF future. Of course, Powell is caught here in the dilemma of trying to write the future while also providing relatable content. Hence, we see Mafalda struggling against a very recognisable family upbringing (there is a great one-liner describing her mother which I won’t spoil for those who haven’t read it yet).

While, despite a complex plot, the politics of the novel are fairly straightforward, e.g. the Jzatian baddies are satisfyingly Brexity and Trumpian, Powell always demonstrates a strong sense of what is at stake. With the Arks offering fully automated space communism, you’d think humanity would be satisfied with feeling the utopian love, right? Of course not! Half of them are too preoccupied with trying to replicate the outdated economic and religious systems of long-gone Earth. Some have even left the Arks to become ‘rich’, as one cheerfully informs Mafalda. ‘But we live in a post scarcity society,’ she replies, only to be told that there are some things only money can buy. Power, authority, the right to control other people’s lives; all the usual things that sociopathic arseholes want. As Powell understands, these people do actually have to be stopped.

Wole Talabi, Shigidi And The Brass Head Of Obalufon (Gollancz, pp.)

This noirish thriller, jam packed with sex and magic, is a welcome shot to the system. Following a London-set cold open, clearly happening in the immediate aftermath of some kind of action that has gone badly wrong, the novel reverts three days, in the first of many time hops and flash backs, to a Thai resort. Retired Yoruba nightmare god, Shigidi, and succubus, Nneoma, are bickering on the beach as to whether they should invite the tall, toned and tattooed woman sitting on a pink teach towel nearby back to their chalet so that they can find out what her spirit tastes like, when they realise that her place has been taken while they weren’t looking by Olorun, elder god and chairman of the board of the Orisha Spirit Company, who offers them a special, urgent job, which will clear their debt with him and earn them an additional big bonus.

Indeed, the gods are on hard times, caught in the same web of neoliberalism as everyone else. The Orisha Spirt Company Board has not long voted to cut down the evil forest to make way for a shrine to cinema. As Shigidi reflects, ‘that was the way the spirit business was going. Evil forests are out, Nollywood is in’. Talabi gets the satire pitch perfect in the passages exploring the internal dynamics and workings of the Spirit Board, including a very entertaining depiction of a boardroom coup at the annual meeting. I particularly enjoyed the early sequence revealing the distinctly unglamourous nature of Shigidi’s job while still employed by the company, as he struggles to collect two spirits during the course of a single night. This becomes complicated when he encounters Nneoma, for the first time, in bed with the woman, whose spirit he needs to complete his quota. Once they have got over their initial reactions to this situation, they strike up a partnership and go into business on their own. Part of the pleasure of these sequences is, as Gary Wolfe noted in his review of Shigidi for Locus, the way that the language of corporate culture is deployed to comic effect: ‘a scheme that goes awry, for example, is an ‘‘unforeseen process deviation’’’.

There’s a lot more – including Aleister Crowley at large in twenty-first-century London – going on in this novel, all of it enjoyable. Shigidi is a memorable protagonist and Olorun is also great fun, but it’s Nneoma who leaves the greatest impression: ‘If you gaze long enough into the eyes of a succubus, the succubus gazes back into you’. Indeed!

Juliet McKenna, The Green Man’s Quarry (Wizard Tower Press, Kindle ebook edition: 355 pp.)

Daniel Mackmain, the son of a dryad and human agent of the Green Man, is charged with solving the mystery surrounding the deadly appearances of a mysterious giant black panther. Early on, there is a comment about such sightings always being attributed to the ‘Beast’ of whichever nearby location begins with ‘B’, such as ‘Beast of Bodmin’. Of course, living in Aberystwyth, I immediately thought of the ‘Beast of Borth’ but alas this particular Green Man novel doesn’t venture into Wales. It does go to plenty of other places, though, and brings in a number of topical themes for more rural areas, including ‘county lines’ drug dealing and the difficult economic climate for tourist destinations and guest houses. The combination of a very English pragmatic, matter-of-fact style – the practically minded Mackmain has zero tolerance for fools – with an ancillary cast of dryads, hammadryads, naiads, mermaids, sylphs, wise women, cunning men and others creates a very distinctive effect. At times, the novel reads like a functionalist anthropologist account of the weirdly symbiotic relationship between humans and non-humans in the ‘matter of Britain’.

I’m a fan of this series, of which this is the sixth instalment: once you have adjusted to the realist style I’ve described, they work nicely as quirky no-nonsense supernatural mystery-thriller stories. Don’t worry if you haven’t read any of the others. It’s fine to start here. McKenna takes care to provide you with the information you need to know and the relevant details about the recurring characters (but without providing spoilers for the other novels). This is not to say that there is no progression: the books are getting longer, and we are gradually being introduced to a wider map of Britain, with The Green Man’s Quarry including extended excursions into Cornwall and Scotland. I get the sense that the scaffolding is being put in place for even more wide-ranging plotlines with higher stakes. So read this and then be sure to catch up on the other novels before the next one comes out.

Christopher Priest, Airside (Gollancz, 297pp.)

This is an abridged version of a review which first appeared in ParSec #8 (Autumn 2023), pp.67-8:Priest’s latest novel is according to its press release ‘a gripping speculative historical novel, grounded in the golden age of film. Perfect for fans of true crime, conspiracy theories and SF that is chillingly close to reality.’ Apart from the last part, this has the effect of making Airside sound like a James Ellroy novel. It led me to consider whether Airside, which is beautifully packaged with a stylish retro cover design, is perhaps what an Ellroy novel would be like if written by Priest from a more oblique British perspective. The protagonist, film critic Justin Farmer, who is given an age and background similar to Priest’s own, finds himself compelled to cherchez la femme, Hollywood star Jeanette Marchand, with the twist that she disappeared in 1949, never being seen again after disembarking from a cross-Atlantic flight at London Airport. While the plot unfolds in classic cinematic manner – I was reminded at several points of Hitchcockian camera angles – there is also ample opportunity for the reader to indulge themselves in an enticing mix of film history, gossip and speculation.

However, Airside is just as much concerned with air travel and airports as it is with film. In particular, the liminal experience of being airside – beyond the security and passport controls – is explored fully through Farmer’s increasingly unsettling experiences attempting to travel between a seemingly unending series of international film conferences. It is possibly not a good idea for anyone prone to anxiety at the thought of not making it to the departure gate in time to read thisnovelimmediately before travelling.

Airside is a superb achievement, in which Priest distils his accumulated writerly craft to produce a novel that charts the uncanny qualities shared by airports and cinema, which are both portals to other realities. Airside or screenside, we don’t always come out as we went in. By capturing such uncertainty before we can blink it away as a trick of the imagination, Priest holds open possibilities that are disturbing but also potentially transformative for those prepared to risk losing themselves amidst the fleeting joys of the world.

(You can read the full version of this review as part of the post I wrote in response to Priest’s passing earlier this year.)

Discussion: This shortlist provides a nice mix of different styles and types of novel. That said, it would have been good to see at least one other book by a woman writer in contention given that 2023 saw a wide range of excellent novels from across the genre, such as Nina Allan’s Conquest, Lauren Beukes’s Bridge, Ann Leckie’s Translation State and Emily Tesh’s Some Desperate Glory. However, there is no question that the shortlist forms an entertaining set of books to read. I’ve no idea who is going to win though. For the first time in five years – during three of which he has won – Adrian Tchaikovsky is not on the shortlist. Gareth Powell is also a very popular writer, and a former winner, but all of these novels will have their supporters. As is often the case, we’re comparing very different works with each other. I don’t feel I can predict the winner and, as is my normal practice, I’m not going to rank these books in order; they are all very special to some readers. I was tempted to give my first vote to Airside because, aside from the fact that I have always been a fan of Priest’s work, it provides an ingenious and satisfying blend of text and found-text (newspaper articles, book chapters, film reviews etc within the world of the novel but crossing directly over with our contemporary world). It is also the sad truth that this is the last opportunity that we’ll get to vote for a novel by Priest and no doubt some people will take that opportunity. However, it might also be the once and only opportunity that we’ll get to vote for the amazing non-patriarchal trans version of the biblical story that is Him. I don’t know if it will win but I gave it my first vote. Let’s see what happens at the Awards ceremony.

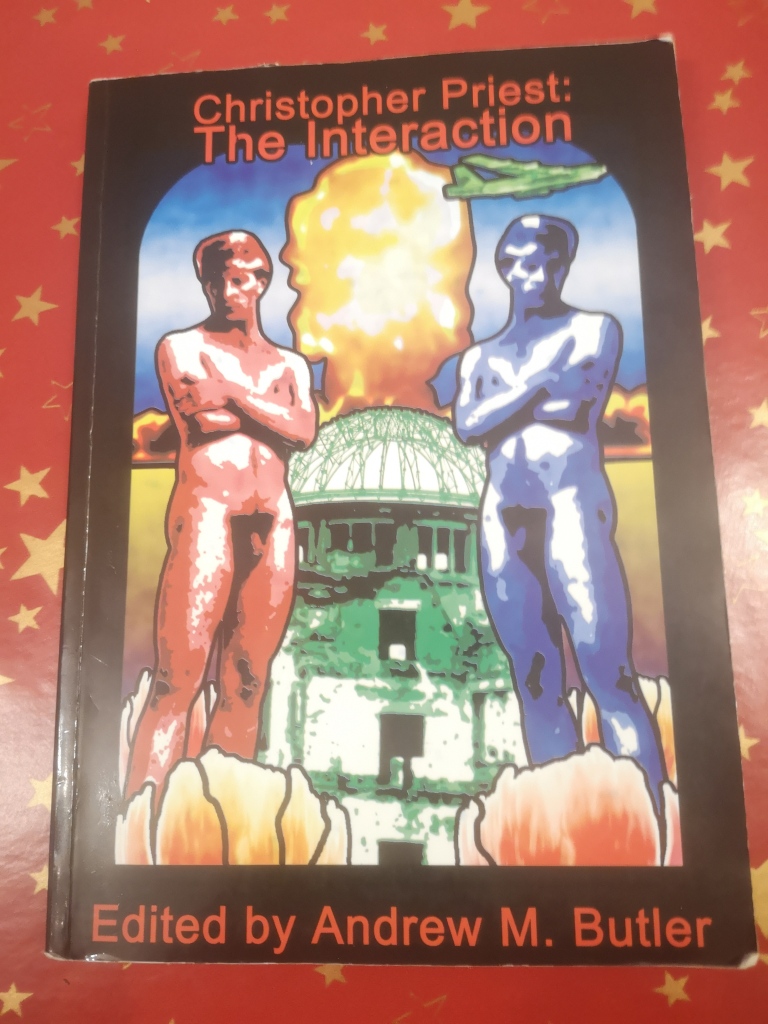

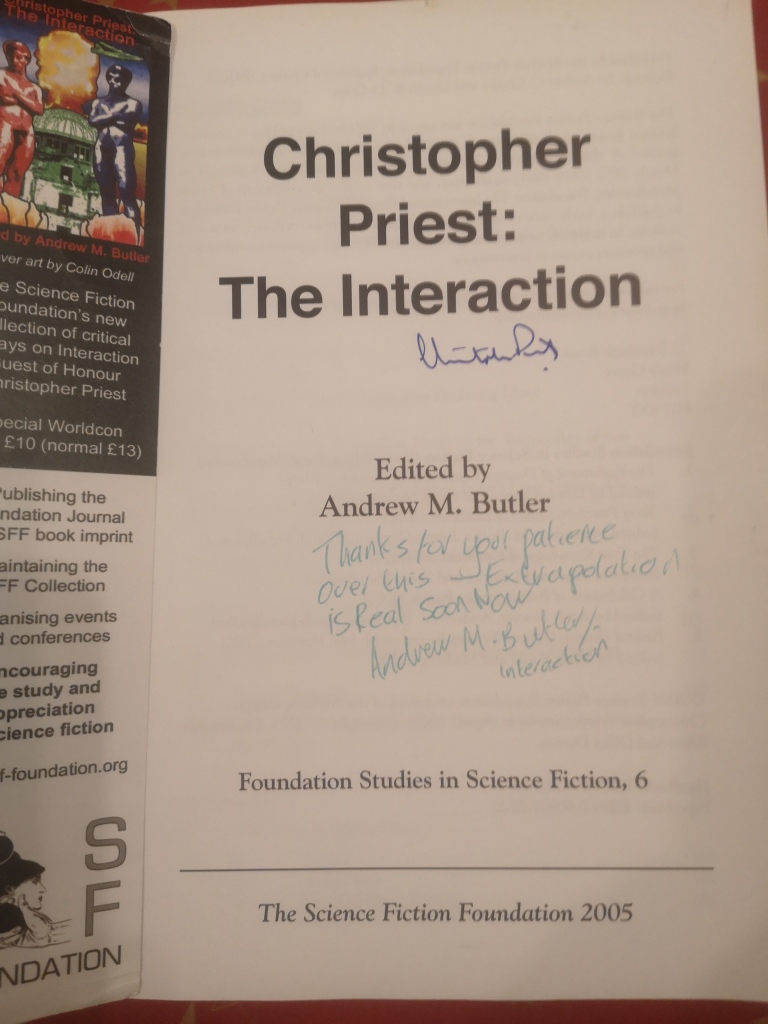

In my recent post, ‘Christopher Priest: A Remembrance’, I said I would find and post the text for my chapter, ‘Priest’s Repetitive Strain’ in the collection of essays on his work that was launched at the Glasgow Worldcon in 2005, when he was Guest of Honour. This was originally published in Andrew M. Butler, ed., Christopher Priest: The Interaction, Foundation Studies in Science Fiction 6, London: The Science Fiction Foundation, 2005, pp. 35-51. I have simplified the referencing, altered some punctuation and added a couple of clearly identified editorial comments. I still like this although I’d probably write it in a less compressed, more discursive style today and enlarge on some of the points and comparisons.

… the book is extremely badly written. It’s too long for its subject matter. The depiction of the characters is sketchy, and only the most shallow of motives are attributed to them to explain their actions. Your storytelling ability is not strong. The text changes direction unexpectedly. You do not acquit yourself well in the writing … Your vocabulary is restricted and there are too many repetitions.

The above justification is given by Gordon Sinclair, the head of a shadowy private company delegated to handle censorship for the Home Office, as the reason for the suppression of Alice Stockton’s manuscript in The Quiet Woman, Christopher Priest’s 1990 novel of a near-future Britain. Little does it avail Alice to complain ‘But those are literary judgements! … this is nothing to do with the book being subversive’: the subtext is that such judgements are always political. It is not by accident that the verdict reads like a satirical description of one of Priest’s own novels. The capacity of his characters to fade from visibility or consciousness or even the text itself, as conventional narrative is thwarted at every turn, is matched only by his own apparent invisibility – despite winning several notable prizes – within the public sphere and to the eyes of academia in particular. One way of explaining this lack of recognition for undoubtedly one of the finest British writers over the last thirty years would be to employ terminology from his own fiction: he is simply too ‘glamorous’ to be noticed. That is to say that Priest’s public invisibility is not simply a product of the well-known perfidy of mainstream critics and cultural commentators but has also become a matter of choice concomitant with the years of diligent practice spent honing to perfection a natural talent for misdirection. The most explicit fictional acknowledgement of this interpretation can be found in The Prestige, his mesmerising story of feuding turn-of-the-century stage magicians. Consider the following tantalising passage in which one of the main protagonists, Alfred Borden, compares the act of writing with that of staging an illusion:

I have misdirected you with the talk of truth, objective records and motives. Just as it is when I show my hands to be empty I have omitted the significant information, and now you are looking in the wrong place.

As every stage magician well knows there will be some who are baffled by this, some who will profess to a dislike of being duped, some who will claim to know the secret, and some, the happy majority, who will simply take the illusion for granted and enjoy the magic for the sake of entertainment.

But there are always one or two who will take the secret away with them and worry at it without ever coming near to solve it.

Not surprisingly, this challenge of ‘solving’ Priest’s ‘secret’ meaning has proved irresistible to critics. For example, David Wingrove has contended that Priest’s unifying theme is ‘the idea of Man separated and at a distance from reality’ (‘Legerdemain: The Fiction of Christopher Priest’, Vector 93, 1979), only to be disputed by Paul Kincaid: ‘Priest’s theme is not to show Man separated from the real world, but to show the psychological effects of such a separation. Throughout his work … a healthy mind … is consonant only with an involvement in the real world’ (‘Only Connect: Psychology and Politics in the World of Christopher Priest’, Foundation 52, 1991). Yet what are these ‘themes’ and ‘realities’ but the ‘talk of truth, objective records and motives’ that Priest warns us against? Such judgements are also political. How then can we read Priest without falling into these traps? The approach taken here will be to consider the developments in Priest’s fictional practice across his career as attempts to avoid exactly those traps and, therefore, as providing a model that we can adapt towards a practice of active readership.

The question of ‘separation’ is explicitly addressed by Priest in his most recent novel, The Separation, in which twin brothers Joe and J.L. Sawyer ‘separate’ into alternate historical tracks during the Second World War. While the book is dedicated to Kincaid, it flatly contradicts his thesis that Priest’s theme is the necessity for involvement in the real world, by depicting history – and specifically British war and postwar history – as a constructed ‘reality’ that not only must be escaped, but also remade (see Hubble, ‘Virtual Histories and Counterfactual Myths: Christopher Priest’s The Separation’, Extrapolation 48: 3, 2007). Hence the bomber pilot, J.L., repeatedly wakes from a crash – which is fatal to him in Joe’s universe – to successively modified futures before he finds himself in the world where the allies won the war, while pacifist Joe’s repeated awakenings from his own accident – fatal in J.L’s universe – and after other events such as the bombing of Coventry, can be seen as an eventually successful attempt to wake up to the peace which emerges in his world with the signing of an armistice between Britain and Germany in May 1941. However, in the final twist, J.L. rejects even this alternate history of peace, as the book closes with him ‘dreaming of waking to a better future’, which by implication is outside ‘history’.

This process of repeatedly working through scenarios until they are mastered bears a striking resemblance to the process of ‘repeating and working-through’ that Freud regarded as central to psychoanalysis, where the challenge facing the analyst is to bring to consciousness that which has been repressed by the patient. The analyst treats repression by inducing a compulsion to repeat so that the patient ‘acts’ out what has been repressed as a ‘piece of real life’ (Freud, ‘Remembering, Repeating and Working-Through’). A cure can be achieved by having the patient continue this repetition under analysis until the point when what has been repressed no longer represents a threat to ego stability. It can be seen that Priest’s protagonists undertake something like a self-analytic process by submitting to their own compulsions to repeat.

Freud generally considered fiction to be a form of wish fulfilment falling completely within the field of the pleasure principle – the corrective mechanism which acts to keep the level of excitement and agitation resulting from external or internal stimuli to as low and stable a level as possible, exemplified by the pleasure of the sexual act which resides in the ‘momentary extinction of a highly intensified excitation’ (Freud, ‘Beyond the Pleasure Principle’). In the well-balanced individual, the pleasure principle is supposed to be subordinate to the reality principle, which postpones immediate satisfaction in favour of greater satisfactions in the long term. Yet it is still the pleasure principle which forms the primary defence mechanism for protecting the ego from trauma by repressing those internal excitations which would otherwise overrun it. Thus, it is the resistance of the pleasure principle that has to be circumvented by the compulsion to repeat during the psychoanalytic encounter in order to effect the cure to the trauma. Freud explained how this was possible by arguing that the compulsion to repeat was an infantile stage of ego defence mechanism that was normally superseded in maturity and only resurfaced if the pleasure principle was overwhelmed. This developmental argument can be illustrated by the classic example of the child who compensates for the mother’s absences by staging the disappearance and return of toys within his reach. The repetition of a distressing moment does not accord with the pleasure principle but rather allows the child to attain an active role in place of his normal passive position. Freud concluded that this infantile stage was a necessary precursor for the subsequent adoption of the pleasure principle and, later still, the reality principle. What he did not consider was the alternate possibility that this mastery through repetition might be preferable to the developmental stages that are supposed to succeed it. This is the radical idea that has been developed by Priest in his most recent fiction, where the goal is not just to escape from ‘history’ but from all forms of ‘reality’.

It was not always so. While the condition of separation has affected Priest’s fictional protagonists since 1970, with repeated use of the term in his first novel Indoctrinaire, it was initially depicted as a form of wish-fulfilling escapism and, as Kincaid argues, the stance of the early books (although, as we shall see, it is only strictly true of the first two novels) was implicit criticism of these characters for their lack of commitment. The key to understanding this transition, from a condemnation to a celebration of separation, is to be found in the way that the condition is associated with a specifically British experience. For instance, The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction suggests that the ‘haunted lassitude’ expressed by the hero of Inverted World is characteristically British. In this vein, it is possible to read Priest’s early novels as an indictment of Britain for itself existing in a state of separation from history or as having become detached from the reality principle. His creation of alternate histories in the 1970s – especially Fugue for a Darkening Island and A Dream of Wessex – represented an acting out of what had been repressed and can be seen as an attempted analytic cure designed to jolt history back on track and re-establish the possibility of British agency. A version of this idea is still evident as late as The Quiet Woman,where the separation of biographical writer Alice from the outside world is gradually revealed as she comes to realise that she has been drawing ‘on the events of history without involving herself with the idea that history actually had to be made’. However, Alice’s attempts to regain agency are mirrored by those of the monomaniac Gordon and the novel’s parallel endings suggest that the liberal solution of ‘only connect’ – perhaps implied in the earlier novels, as Kincaid argues in ‘Only Connect’ – is no longer sufficient to resolve the British problem. It is this ongoing concern with the state of the nation that has led to the major shift in the psychological and philosophical underpinnings of Priest’s fiction so that separation is no longer a problem to be cured but a point of departure.

Priest has acknowledged this development in his fiction, albeit in typically backhanded manner: ‘Although I seek to avoid categorisation of my books, slipstream can be a useful identifier’. He has variously identified slipstream as ‘an interest or obsession with thinking the unthinkable or doing the undoable’ and ‘a different way of inquiring into the familiar’. But it might also be described as a type of fiction that does exactly what Freud thought impossible in the aesthetic field by going beyond the pleasure principle to those compulsive and repetitive ‘tendencies more primitive than it and independent of it’ (‘Beyond the Pleasure Principle’). Such a transition involves crossing the boundary identified by Brian McHale in Postmodernist Fiction as that where ‘intractable epistemological uncertainty becomes … ontological plurality’. McHale illustrates this transition by citing the poet Dick Higgins’s examples of epistemological questions – ‘How can I interpret this world of which I am a part? And what am I in it?’ – and ontological questions – ‘Which world is this? What is to be done in it? Which of my selves is to do it?’. McHale’s intention is to differentiate between the respective dominant concerns of modernist and postmodernist fiction, but it is his correlative examples of popular genres that are of particular relevance to us here: ‘the detective story is the epistemological genre par excellance’, but ‘science fiction … is the ontological genre par excellance’. While McHale seeks to show the staged transition of modernist concerns into postmodern ones across the individual careers of different writers such as Samuel Beckett, Alain Robbe-Grillet and Thomas Pynchon, it is possible to demonstrate a comparable transition for Priest: firstly, from epistemologically orientated genre sf to ontologically oriented sf and then, secondly, beyond sf itself, where we find not the mainstream but the slipstream.

In Billion Year Spree, Brian Aldiss coined the term ‘cosy catastrophe’ to refer to the British postwar disaster novel epitomised by John Wyndham’s The Day of the Triffids. The problem with the term is that too many of the books it is supposed to refer to, including Wyndham’s, are far too ambiguous to warrant the generalisation. Even Aldiss uses the term as a kind of imaginary benchmark from which the magnitude of deviation can be measured. Thus, he describes John Christopher as ‘semi-cosy’ and (in Trillion Year Spree) Priest’s Fugue for a Darkening Island as ‘far from being a cosy catastrophe’. This was Priest’s second novel, in which a suburban family disintegrates amidst the savage civil war triggered by the arrival of two million African boat people in England (see Hubble, ‘Five English Disaster Novels, 1951-1972’, Foundation 95, 2005). However, its predecessor Indoctrinaire had also incorporated elements of the disaster genre. Specifically, the Third World War breaks out in July 1979, with England being destroyed by nuclear weapons on 22 August 1979 – a fate which the hero, Allan Wentik, deliberately chooses to share.

The distance travelled across the genre from the imaginary Wyndhamesque template can be illustrated by examining some different representations of the stock moment of the hero awakening in a hospital bed: Wyndham’s Bill Mason peels off his bandages to find himself sighted and sane in a blind and insane world, before venturing out manfully; J.G. Ballard’s Donald Maitland, in The Winds from Nowhere (1962), hallucinates himself as blind and in hospital and then realises that he is in fact sighted and sane and not in hospital; Priest’s Wentik comes round to find himself two hundred years in the future in Brazil and has sex with the nurse. Of course, it is this wish-fulfilment fantasy that Wentik ultimately rejects by deciding to go back and die with England. The logic behind this is that to live in the cosy future would be to accept the destruction of his family and the ‘whole set of memories and impressions and images’ which made up his identity and, therefore, it would be ‘to condone the removal of a part of himself’: exactly that condition of separation which haunts Priest’s oeuvre. But this is ‘just one half of a two part problem’ – the other being whether Wentik can choose to believe that his world is still going on regardless of the fact that he has been told otherwise: ‘To have a belief indoctrinated externally is one thing, but can a person indoctrinate himself by simply wishing to believe something?’ This is the central question of the book – hence the title – and it also one that runs throughout Priest’s subsequent work. Here, the answer is firmly in the negative and a position which we know is endorsed, albeit in a modified form, in his later fiction is identified squarely with Jexon, the principle character of the future society: ‘the man was a meritocrat-advocate, interpreter and delineator of a society he had abstracted himself’. Against this, Wentik’s ‘main preoccupation was to get back to what he knew as a normal life’. The qualification ‘what he knew as’ merely serves to indicate the limits of an epistemological framework which is still determined in the last instance by rationality. Within the confines of such a framework, the only means of avoiding the alienated condition of separation is through death (Edit: in other words, Indoctrinaire illustrates the Freudian death drive – also a factor in Ballard’s novels of the 1960s, which were influences for Priest). This uncosy resolution to the epistemological impasse necessitated by the rejection of wish-fulfilment characterises Priest’s early fiction.

While this confirms our dissatisfaction with the ‘cosy catastrophe’ paradigm, it does fit with Aldiss’s alternative and less well-known designation of the disaster sub-genre as ‘anxiety fantasies’ (also in Billion Year Spree). This phrase contains a very fruitful ambiguity. If we think of fantasies as being analogous to dreams, it is possible to take anxiety fantasies as either fantasies that fulfil wishes (such as the cosier kind of catastrophe) or fantasies that master the unconscious to a different end by drawing on psychical resources preceding the establishment of the pleasure principle (see Freud, ‘Beyond the Pleasure Principle’). While both strands are often in evidence, it is clear that the sub-genre as a whole follows the Freudian model of ‘repeating and working through’: with the breakdown of the reality principle, compulsion resurfaces and eventually sufficiently masters chaos to the point that a new reality principle forms, as in The Day of the Triffids for example.

In Priest’s work, this compulsion is perhaps most clearly present in the symbolically named Helward Mann, the hero of Inverted World, in which a city has to be kept moving relentlessly across hostile terrain by a continuous process of laying down and taking up huge rails, supervised by ‘guilds’. This starts like a classic coming-of-age story in which the young apprentice masters a number of setbacks through sheer doggedness and thus proves himself to his guild superiors as sufficiently driven and determined to be accepted as an equal. However, confounding our expectations, he remains true to this code even when it becomes obvious to everyone else in the city that there is no need for it to keep on moving, which has in any case become no longer possible. Ironically – considering this subversion of a classic plotline – the novel has been described as ‘pure’ (The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, third edition), or even ‘first-rate hard’ (Trillion Year Spree), sf. This is to miss the point that although the counter-intuitive physics, in which an infinite world resides within a finite universe, is brilliantly realised, the sf is neither predominantly pure nor hard but distinctively metaphorical and psychological. The subtext of the physical inversion of planet Earth – the origin of the expeditionary forces from which the inhabitants of Inverted World are apparently descended – is a political inversion of colonialism. Whereas on Earth, civilisation depended on a system of economic inequality which allowed the rich and powerful to monopolise commodities, in the novel it is a surplus of food, fuel and raw materials which allows the civilised mobile city to exploit ‘native’ manpower: ‘the process was inverted, but the product was the same’. The apparent physics of the world, in which the city must keep moving because otherwise a perpetual southward drift will move it so far from ‘the optimum’ that it will be subject to spatial and temporal distortion, naturalises the compulsive drive behind civilisation and colonialism. This analogy is particularly cleverly brought out through the final initiation rite undertaken by aspiring guildsmen: they must escort ‘native’ women back ‘down past’ to their home villages after the spells they have spent in the city for breeding purposes. The unspoken element of the initiation rite – and therefore of becoming a man – is the sexual exploitation of the women, which is portrayed as a natural outcome of the physical distortions encountered as they spontaneously burst from their clothes: ‘Rosario split the seat of her trousers. One of Lucia’s buttons popped off … and Caterina tore the fabric of her shirt down both seams below her armpits’. More specifically, the book can be read as a metaphorical portrayal of postwar Britain. The guilds are the public-school establishment, driven by their ideal of service; the armed attacks on the city carried out by the native ‘tooks’ represent the various independence movements across the Empire (edit: although I’m now wondering if this should be read as a playful Tolkien reference), filtered through the imagery of Vietnam; and the internal dissident movement of ‘terminators’, who want to stop the city, are the 1968 generation.

What Mann resents most is the way that the combination of external and internal attacks lead to a loss of self-belief: ‘Now the tracks were being built in spite of the situation with the tooks, rather than in the way I now understand the motivation of the city to be derived, from an internal need to survive in strange environment’. Therefore, Mann’s position can be seen as one that privileges inner compulsion over the external demands of ‘reality’. The famous twist in the novel serves to make this clear. It transpires that the city is in fact on Earth, having been founded by a British particle physicist and set on a course starting in China some two hundred years previously, following a ‘natural window of potential energy’ across the surface of the Earth which serves to power an artificial energy field around the city. However, we also learn that this ‘translateration generator’ has the side-effects of altering perception and creating genetic defects. When these facts become known, the people of the city turn off the generator and allow their perceptions to revert back to the reality principle. Ontological uncertainty seems to be resolved back into an epistemological framework with only one problem: Helward Mann. He alone refuses this alternative and instead dives off the unfinished bridge, which the city guilds have been trying to build across the Atlantic. As with the ending of Indoctrinaire, the logic is that destruction is preferable to the state of separation (from all previous impressions, memories and identity) which would follow from having to accept a different ‘reality’. However, there is one final twist in the last sentence: ‘As darkness fell I swam back through the surf to the beach’. Although ambiguous, this is a more upbeat ending than those of the previous two novels and suggests that the choice confronting Mann is not simply that of old and new realities. Indeed, there is an alternative: the time Mann spends ‘up future’ where the temporal distortion means that ‘a day spent lazily on the bank of a river wasted only a few minute’s of the city’s time’. The attainment of this ‘terrain where time could almost standstill’ is only achieved by the partial separation of being distanced from the ‘reality’ of the city, without switching to the alternative ‘reality’ of 22nd Century Earth, which would entail an irrevocable separation. This rather fragile possibility suggests a future beyond the ‘better an end in horror than horror without end’ closing of Indoctrinaire.

The narrative device of the time loop, which features in various forms in all of Priest’s early novels, is the great contribution of genre sf to the problem of how the complex potentiality of utopia can be represented. Priest’s greatest success with this approach is A Dream of Wessex. Julia Stretton’s desperation to escape the terrorism, police road blocks and traffic congestion which characterise the disintegrating Britain of the 1970s, motivates her participation in a collective projection of a future soviet Wessex. Here, she is caught between the fascinations of two compulsively driven males, David Harkman and Paul Mason, who represent alternative rejections of the reality principle. The complex resolution to the novel is achieved by a sophisticated time loop in which the participants of the future projection are talked into projecting themselves further into the future by Paul. Most of them return to the 1977 starting point, but Paul disappears into some future reality of his own while David remains in the projection, where Julia manages to rejoin him in an undeniably happy ending. The closing descriptions of David surfing through the drowned valleys of England are quite explicit in their demonstration of his achievement as a psychological one, as he experiences a sudden lapse:

Beneath him, the wave, the cliffs and the sea had vanished. He was floating above countryside … There was a road down there, and he could see a line of traffic moving along it …. He felt he was about to fall, and he thrashed his arms and legs as if this would save him …. At once his motion ceased, and he was suspended again in the air, although noticeably lower than before. Now he could hear the traffic on the road … Harkman wished himself higher … and at once he felt the pressure of the wind on his back, and he soared upwards. When he had attained his former height, he made himself turn around again […]

What he saw had no meaning for him: it was the product of some unconscious wish that he could not control …. It was something that had excluded him, something that he had in turn rejected …. Because it was from the unconscious past, unremembered, it was at once wholly intimate and voluntarily relinquished. It was the landscape of his dreams, a world that was not real, could not ever become real.

As once before, when he had unconsciously rejected this phantasm from his life, Harkman exercised a conscious option, and expelled the dream.

Therefore, rather than David and Julia’s escape being a wish-fulfilment fantasy, it is ‘reality’ that is shown to be the wish-fulfilment fantasy, as the limits of the epistemological are transcended in a fully ontological world and the stable projection of a utopian future becomes possible for the first time in Priest’s fiction.